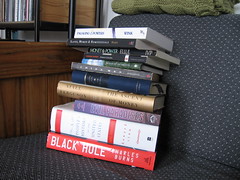

I noticed that every book I’ve read this quarter is one that I physically own. Our post-marriage bookshelf (or more appropriately, our bookshelves plus random piles of books), are a gold mine, especially after Christmas, birthdays, routine trips upon my insistence to the Last Word Bookstore and a year of using

Paperbackswap. Two books are missing from this photo because they are at my office. I’ve started keeping personal books at my office, because there’s really no space in our current apartment. Sigh. (Wait, three books are missing. I suppose one has just been misplaced....)

Seeing all these books stacked on top of one another reminds me of how much I love the physicality of books—the binding, the texture of the cover, the smell of the pages. Hannah Arendt describes the printed book as the “transformation of the intangible into the tangibility of things,” something that is lost in the gadgetry of Kindles and the liquid crystals of internet text. From Christine Rosen’s

People of the Screen:

As he tried to train himself to screen-read—and mastering such reading does require new skills—Bell made an important observation, one often overlooked in the debate over digital texts: the computer screen was not intended to replace the book. Screen reading allows you to read in a “strategic, targeted manner,” searching for particular pieces of information, he notes. And although this style of reading is admittedly empowering, Bell cautions, “You are the master, not some dead author. And that is precisely where the greatest dangers lie, because when reading, you should not be the master”; you should be the student. “Surrendering to the organizing logic of a book is, after all, the way one learns,” he observes.So for now, no Kindle for me. Let me submit to the mastery of the printed text! I’m already susceptible to skimming. Besides, I don't get along with gadgets-- I drop my cell phone frequently and lose it for days on end...

In any case, in the past, I usually review books right after I read them. This time around, I procrastinated and ended up writing most of these in the last two weeks, so they may be a little lacking in quality. At the very least, I hope they can give you an idea of what the book is about and whether or not you might want to read them. Italicized books are the ones that I did not finish.

Rating scale from

Goodreads * didn’t like it

** it was ok

*** liked it

**** really liked it

***** it was amazing

Fiction* or ** The Tin Drum (Gunter Grass) ~ I wanted to like this book, as it’s been compared to two of my other favourites: Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children and Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude. With a trip to Europe planned for the summer, I was also excited to learn about Poland and Germany, as the novel recounts a midget drummer’s childhood and coming of age during the Nazi’s rise and fall of power. But what can I say? I didn’t really like the book. The novel’s language lacked the narrative fluidity that made me love the other two novels (perhaps because it was originally written in German?). The novel’s surreal details were less magic realist (which resonates more with me) and more absurdist in the line of Pynchon (which perhaps because of my cultural background, doesn’t make any sense to me). The novel had several funny and/or insightful passages and I can understand why it has been acclaimed as one of the greatest pieces of German literature since World War II, but to be honest, I can’t say I enjoyed reading it very much.

*** China Men (Maxine Hong-Kingston) ~ I didn’t really get into this book as much as I had hoped. I wrote on Maxine Hong-Kingston’s The Woman Warrior as my senior thesis so I am familiar with her work and style. Hong-Kingston weaves together myth and fact as she recounts the stories of Chinese male immigrants to the United States, from as early as the gold rush and railroad construction to the 1990s. The narratives are detailed, vivid and suggest a mythical historical memory. Her descriptions of the railroad construction by Chinese men and the confusion of the Communist revolution are particularly compelling, but some of the latter stories in the novel were less interesting.

**** Beasts of No Nation ~ After reading the first chapter, I wasn’t expecting to like the book. It was very “loud”, full of yelling and violence and what you’d normally expect from a book about child soldiers. Fortunately, the book did not turn out to be the usual narrative about the horrors of war. Instead, the book explores the psychology of a child soldier amidst the violence of war. What does it mean for someone so young to kill? What does it mean to be both perpetrator and victim?

*** Black Hole (Charles Burns) ~ This graphic novel depicts the spread of a mysterious STD amongst high schoolers in Seattle in the 70s. The disease manifests itself in bizarre physical mutations—tails, mouth, peeling skin etc… The graphic novel is as much as about the initial AIDS as it is about high school social politics, isolation, boredom and rebellion. The artwork is also remarkable as the drawings are also entirely done in black and white strokes (no gray-scale). As a warning for those who are sensitive, the novel has graphic depictions of male and female genitalia.

Non-Fiction**** On Writing Well (William Zinsser) ~ The first section of the book covers general principles for writing well, while the second section describes guidelines for specific types of writing, including business writing, sports-writing, memoir-writing etc.. The book helped me think about how I can better improve both my business writing, my blog writing and my elusive in-my-head magazine articles that have never actually been written. It is also very enjoyable and readable—much less dry than Strunk’s Elements of Style, which I don’t think I ever finished reading.

***** Engaging the Powers (Walter Wink) ~ I haven’t had a five star book in awhile, but this book definitely qualifies as such. Walter Wink writes about the domination system of the world and the spiritual interiority of institutions. Though Wink may fall on the more liberal end of scriptural analysis, his ideas concerning the spiritual core of institutions and the role they play in society, the significance of Christ’s death and the power of nonviolent action provide a much more comprehensive understanding of the world.

*** Reclaiming Capital: Democratic Initiatives and Community Development (Christopher Gunn) ~ Similar to his other book Third Sector Development, Gunn explores ways to reclaim capital for investment and use within a community. To set the context, Gunn describes the way in which capital is internationally mobile and flows to the area of greatest return. Communities who wish to attract firms often do so at their own detriment—lax labour and environmental standards or tax incentives. Frequently, firms who do locate within a community do not provide the benefits promised. For instance, Gunn assesses how little of the economic benefits generated by the opening of a new MacDonald’s restaurant are actually retained by the community. For the rest of the book, he describes the efforts of different community institutions in reclaiming capital for improving their own communities. This book is clear and well-written even for those unfamiliar with economics or development. It is an excellent introduction for thinking more critically about how capital flows in the world and how it affects different communities.

**** Slaves, Women and Homosexuals: Exploring the Hermeneutics of Cultural Analysis (William Webb) ~ Through the examination of three controversial issues in the church historically and/or currently, Webb provides a framework for “the hermeneutics involved in distinguishing that which is merely cultural in Scripture from that which is timeless." He presents a set of 18 or so criteria that can help us determine how scripture texts apply to our current context. He explains each of the criteria and then assesses the three controversial issues in his title in light of those criteria. While his final conclusions on the three controversial issues are important, the book is most valuable for providing anyone with a framework of distinguishing what is cultural and what is transcendent in scripture.

** The Financial Ascent of Money (Niall Ferguson) ~ When I read non-fiction books, I tend to get irritated at the author’s tone after about 100 or so pages. It was a bad sign when I got annoyed at the Ferguson’s writing style after about one paragraph. He writes like a slick modernist, one that firmly believes in greatness of our Western cultural and economic trajectory. However, I decided to give the book a chance and ended up reading/skimming most of it. It turned out to be okay. I expected the book to be focused on currency specifically, rather than all sorts of financial instruments. The book covers the historical development of bonds, stock exchanges, insurance, real estate and derivatives (including the crash of Long Term Capital management). Ferguson’s final chapter describes the influence of finance on the British empire and international relations, including the recent development of Chimerica (China + America). Ferguson goes into great narrative detail describing specific events and/or people—not surprising given that he is a historian. I don’t think he goes into sufficient detail in explaining how the different financial institutions and instruments work. As someone with a business education (is that an oxymoron?), it was okay for me to understand but it may be more challenging for someone who isn’t as familiar with these terms. Not bad, not great. The writer’s tone also became slightly less annoying over the course of the book. He makes a good point of indicating that despite all our mathematical models, our current form of capitalism is subject to extreme volatility—bubbles and crashes—and that history may be as important a lesson as statistics.

*** Eichmann in Jerusalem (Hannah Arendt) ~ I expected this book to be a philosophical and psychological exploration on the nature of evil, but it turned out to be more about the trial of Karl Eichmann in Jerusalem and a historical overview of his rise to power and his orchestration of Jewish deportation in each of the German-occupied nations. The book reads tediously at points, but other sections are fascinating—the Denmark resistance to Nazi orders, the significance of Eichmann’s kidnapping from Argentina by the Israeli Mossad, the desire for Eichmann’s sentence to deliver justice not just for the crimes for which Eichmann was individually responsible but for also for all Nazi crimes against Jews, and the contested fairness of a trial where the judge was Israeli and no defense witnesses were available because no former Nazi would come to testify in Israel. The last chapter provides the best overview and commentary of the trial, with a particular focus on legal and judicial philosophy. If you don’t want to read the whole book, but are interested in the ideas—I would suggest reading the last chapter.

**** Money and Power (Jacques Ellul) ~ From the title, I thought this book would be about people with money and power. However, the book could be more appropriately named the power of money. Ellul first explores wealth in the Old Testament. He examines instances when God used wealth as a reward or blessing, emphasizing that the riches were a gift and a material demonstration of God’s power. Ellul then elaborates on how Jesus completely transforms our relationship to money, especially as He becomes the “Poor One”. Why are the poor amongst us? How must we relate to them? Ellul’s final conclusions are challenging—that Christians should not be in the practice of saving or hoarding, and that everything beyond what they need should be given away. This practice allows one to be freed from serving Mammon (the system of selling and buying) and to “enter” the kingdom of God, where grace and giving reign.

**

The People’s History of the United States of America (Howard Zinn) ~ I had read some excerpts from this book earlier and enjoyed them and was hoping for a insightful critique of the mainstream reading of American history. However, the book (or atleast the parts I read) seemed to list the usual liberal grab bag of events and facts combined with a hefty dose of lefty rhetoric. While a decent introduction to the injustices committed by America to its own people and to others, I don’t think the book provided any astute or significant commentary on either American history or the writing of American history.

***

Evil Paradises: Dreamworlds of Neoliberalism (Mike Davis, Daniel Bertrand Monk, editors) ~ This book is a compilation of essays on the urban and spatial developments of the wealthy in the world. I have read about half the essays-- most of them elucidate not just the stark contrast between the rich and the poor, but also the economic, social, environmental and moral cost of these “dreamworlds” to the poor and to humanity.

**** Commager on Tocqueville (Henry Steele Commager) ~ Despite a somewhat self-preoccupied and unenticing title, the book is excellent. Commager assesses American history in the last century through the set of questions raised by Alexis de Tocqueville, the famous French aristocrat who wrote about America in Democracy in America. Tocqueville primarily was concerned with democracy – especially the tensions raised between liberty, order and equality. He examines issues of slavery and justice, centralization and democracy, military vs. civil power and political equality and economic inequality in America.